Revisiting Akira - Part 1: The Manga

A catalogue of thoughts accumulated while rereading and rewatching Akira...

To begin with a potentially unnecessary disclaimer, I want to clarify that this post will in no way be a comprehensive deep dive into Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira. In fact, I would like to redirect readers to other resources and blogs for those interested in learning more about Akira’s production history and Katsuhiro Otomo as an artist more broadly. One resource I found while prepping for this post was ChronoOtomo, a website that offers what seems to be a very comprehensive timeline of Katsuhiro Otomo’s entire career, including every work he’s published and even press events. It is still being updated now with the most recent entry on the timeline being a talk that occurred between Otomo and mangaka Tadashi Matsumori on June 14th, 2025. The website also includes options to read the timeline in multiple languages, which is nice! I mostly ended up using the site to help me figure out which chapter of the original serialization I was on while re-reading; since all title pages were removed from the tankoban editions by Otomo in order to improve the pacing of the story. There are many other reasons to dive into the site's extensive back catalog of webpages though if that tickles your fancy. Additionally, a second resource that I would like to redirect readers to is the WordPress blog Exploring Akira. Again, this seems like a good fan-made resource for information about both the manga and anime’s production history, as well as other Akira related paraphernalia.

Suffice to say, there is a passionate fan community around this work and its various adaptations. As such, this post is not a retrospective so much as it is an accounting of personal experience–a catalogue of thoughts accumulated while rereading and rewatching Akira after over a decade of not thinking about it much. If that sounds interesting to you, I hope you get something out of this post. Otherwise, I’ll understand if you clicked away to view the two of the other websites I referenced instead.

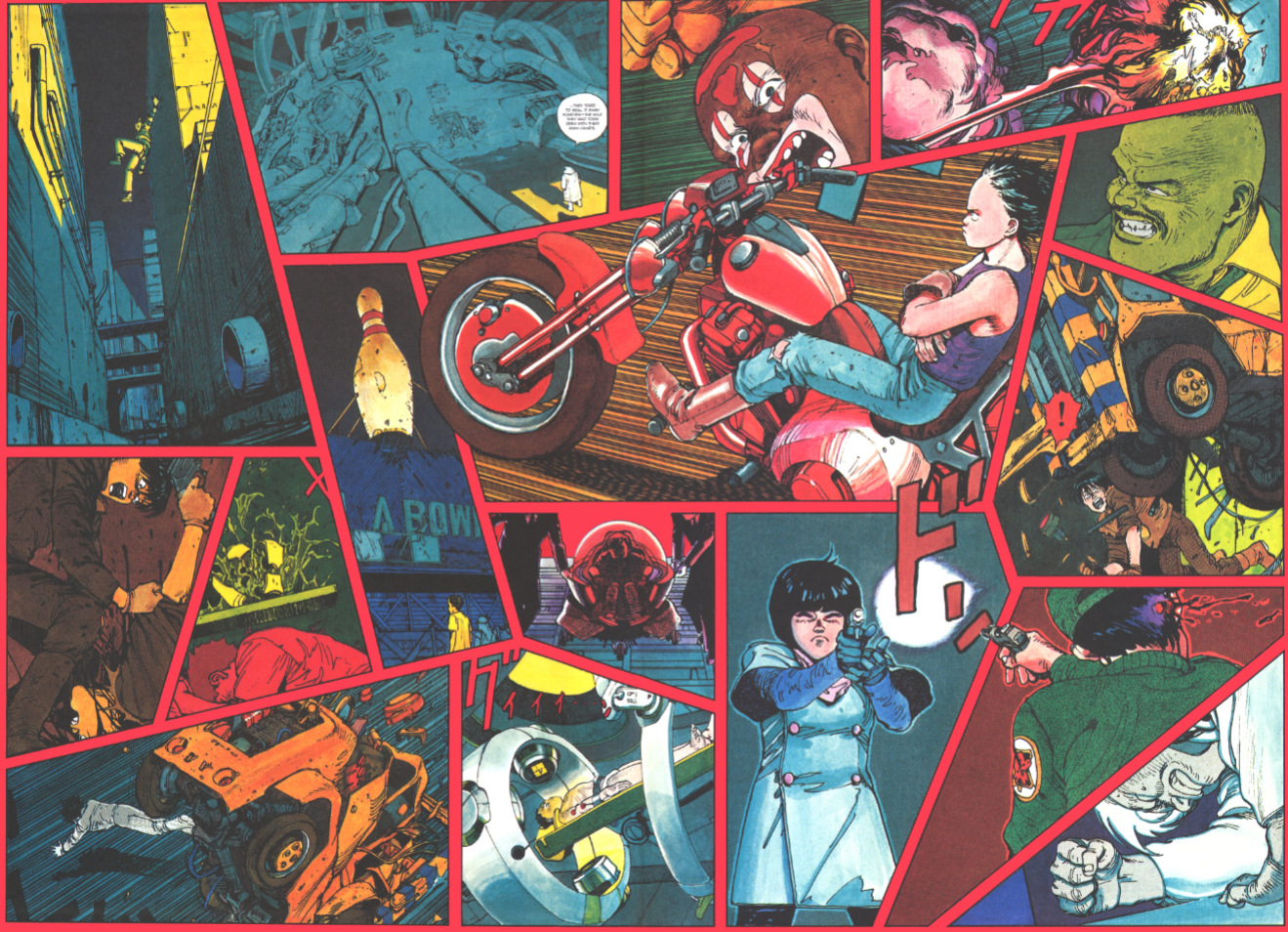

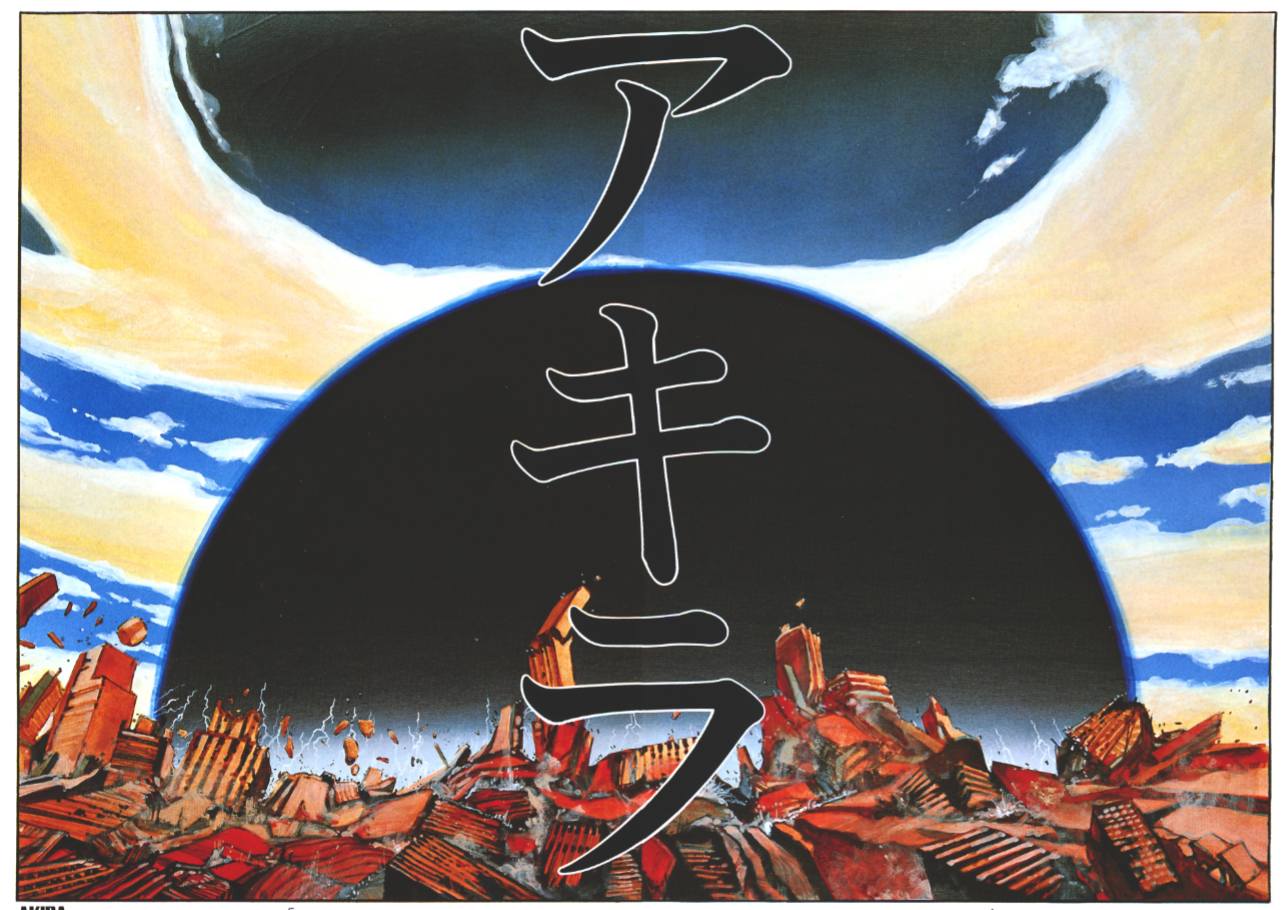

It’s best to kick off the main body of this post by contextualizing Akira and my relationship to it. In case you aren’t aware somehow, Akira is one of the most seminal sci-fi action manga in the history of its medium, especially in terms of crossing over to Western continents. It’s received releases in countless languages and its release in the United States under Epic Comics, an imprint of Marvel, in the late 80’s and early 90’s corresponds with important technological shifts in the medium. As laid out in an Anime News Network interview, the colorist for the US edition Steve Oliff explains how Akira was a pioneering work in terms of computer coloring in comics. Oliff and his team were early adopters of this technology. Some sources even say Akira was the first comic to use this technology, but the aforementioned ANN interview and various other sources I found don’t fully corroborate Akira as specifically the first digitally colored comic by Oliff. Either way, Oliff was awarded the first Eisner for Best Colorist in 1992, in part for his work digitally coloring Akira and several other comics.

So yeah, the comic is intertwined with the history of the medium, not just in its home country, but abroad as well. In many ways, Akira was one of the first anime/manga crossovers to the United States and you still see it referenced in modern day works (the most recent example that comes to mind is the motorcycle slide in Jordan Peele’s most recent 2022 film, Nope). I’ll be diving into some additional elements about the Akira manga’s various renditions in the United States, but I feel this slice of history does a good job at illustrating the importance of this media property.

My relationship and introduction to Akira by comparison is much less complex. I first watched the Akira anime in late middle school. I was drawn to the work due to its ubiquity, but certainly didn’t know about its long history of US publication or really much about it at all. It did leave an impression on me though–enough that I sought out the manga at my local library and was willing to purchase copies of the manga myself later as an adult. That being said, what spurred on this project was my lack of concrete memory around both the manga and anime. Despite being some of the first titles I watched/read when getting into Japanese media, my memories of the plot and characters were pretty threadbare when I started this project. This is especially true of the manga. Back when I first was getting into manga, I read stuff very quickly. Compared to my current manga reading habits, I wasn’t doing a great job at absorbing the visual information on the page. It has also been easily over a decade as well, which definitely has not helped matters.

Still, when I purchased the 35th anniversary boxset, it was done somewhat impulsively. It wasn’t even on sale, I was just curious about trying it out again. I could’ve sought out copies from the local library, but I was swayed by the historical significance of the work in addition to some publication factors I’ll get into later. Suffice to say, there was not a ton of motivation for me to jump into this reread, and the boxset sat on top of my bookshelf for many years collecting dust until last year when I rewatched a completely separate animated film by Katsuhiro Otomo called Steamboy.

Not to go too far off on this tangent, but my rewatch of Steamboy was… an interesting experience to say the least. Like Akira’s manga and anime, the last time I had watched the film was probably in late middle school, maybe even earlier than that. It left a similarly vague, but impactful impression, albeit for slightly different reasons. Even when I was younger, I remember thinking the film was kind of bad. Still, tastes change and when I spotted it at my local video rental store I felt myself drawn to it. Unfortunately, I cannot say Steamboy improved in my estimation, even with my increased cognizance as an adult. The film’s script is a hot mess, to put it mildly, but it did make me even more curious about revisiting Akira. Mainly, I wondered if Steamboy’s thematic incoherence as a work about the evils of the military industrial complex that simultaneously couldn’t help but fawn over the very machines it criticized would be something that came from Akira. Could it be that Akira was maybe not the flawless masterpiece so many have held it up as?

Well, to answer that question, it is often a bad idea to hold any work on such a high pedestal, particularly one as old as Akira. A manga nearly a decade in the making, serialized (mostly) bi-weekly from 1982 to 1990 in Kodansha’s Young Magazine in Japan, it’s a work that has some years on it to say the least. Times change, taste changes, culture shifts–there’s no way a work can hold up flawlessly at this point over 40 years since its initial chapter was published. Still, the work is beloved for a reason, and although it may have faults which I will outline in this post, I want to make it clear that Akira’s status as an important cultural and historic work is not something I’m denying or disputing. Rather, I’m merely outlining the things about the work that resonated with me and that I still find compellingly messy as a modern day reader

One of said things is that aforementioned thematic incoherence that I found so intriguing in Steamboy. To expand upon that point, Steamboy’s plot conflict is driven by a scientist seeking to wield unimaginable technological power. The hubris of the antagonist of that film is his belief that man can triumph over nature, that its power can be wielded without consequence for the sake of military or technological progress.

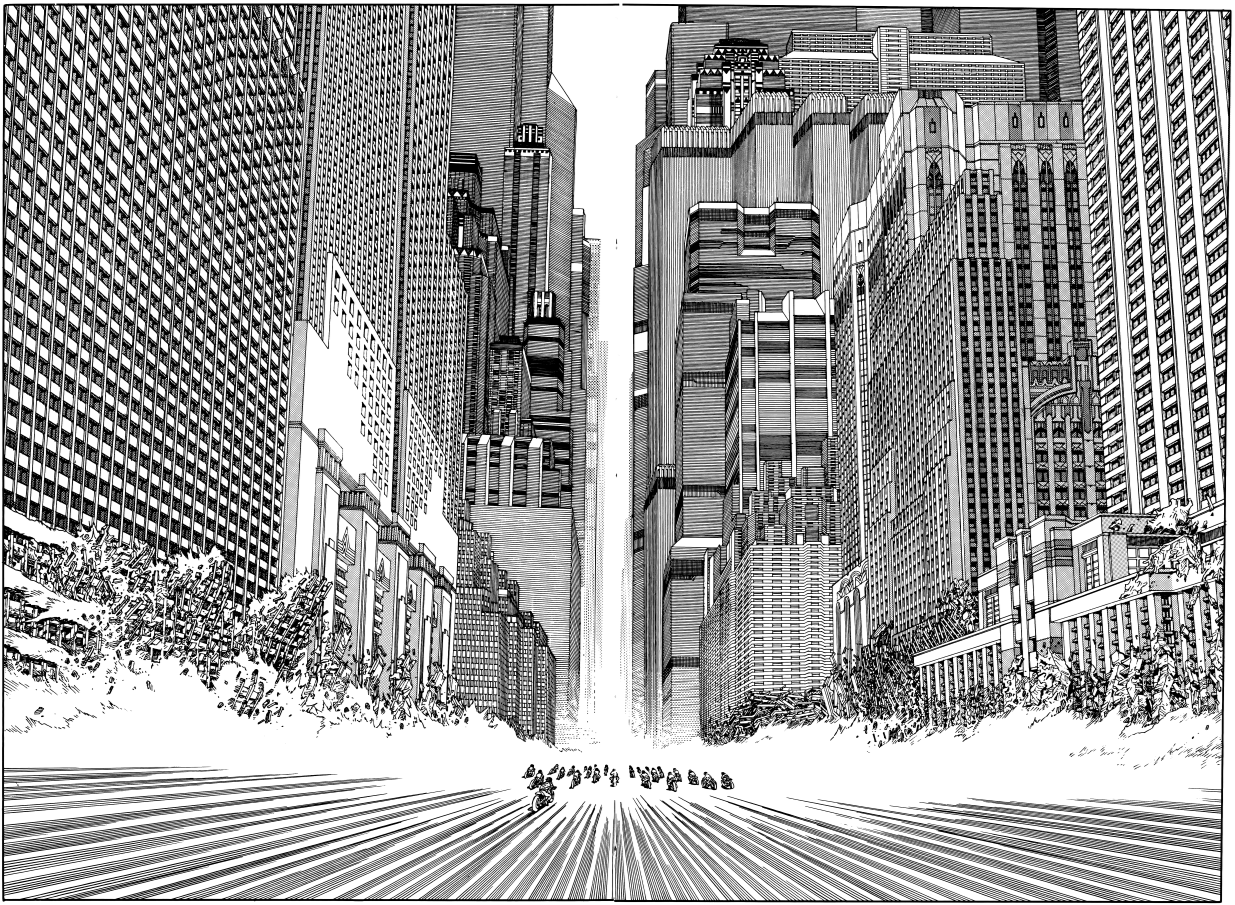

Akira’s central conflict is based around a similar point of tension. In both versions of the story, Colonel Tsukishima and the Japanese government are working on a project to train and hone the powers of children with psychic potential. The disastrous effects of this project are evidenced in the manga and anime’s opening moments as a massive explosion occurs as a result of this experimentation on a subject named Akira (though the reader does not immediately know this is the reason for the explosion). Akira is frozen in cryostasis to prevent another incident from occurring and the catalyst for the main plot occurs decades later in 2019 in the rebuilt city of Neo-Tokyo. Things kick off when Tetsuo, a member of a gang of teenage bikers, collides with an escaped psychic subject labeled No. 26. From here, the military conspiracy is gradually unraveled as Tetsuo’s friend and our ostensible protagonist, Kaneda, gets involved with a group of terrorists seeking to learn the truth behind the Akira project. Meanwhile, Tetsuo is discovered to have psychic potential by the Colonel and his team of scientists, resulting in them awakening his powers to increasingly disastrous consequences.

Like Steamboy, there’s a critique here of the military industrial complex. Even though the military knows that Akira already destroyed Tokyo in the past due to his psychic abilities, the possibility of controlling that power is too enticing to divest from the project. The experiments continue and the Colonel hopes Tetsuo can be a new Akira, one he can control and wield to subdue for his own purposes. In reality, this is complete hubris. Tetsuo, a volatile kid with an inferiority complex built around his relationship to Kaneda, is not the greatest subject for this masterful plan. Again and again throughout the manga, there’s this illustration of the older generation in places of power, represented by politicians like Nezu and military agents like the Colonel, underestimating and failing to control the power of the youth within their society. The children with psychics represent the younger generation–filled with potential and possibility–who self-implode due to being raised in a society that views them as nothing but resources to be controlled and harnessed.

This critique of the older generation and of military power is still relevant today. Not just in the oddly prophetic ways, such as the Olympics being hosted in Tokyo in 2020, but in terms of the political state of its setting. Neo-Tokyo is a hypercapitalist futuristic city ruled by a government easily couped by military leaders and where impoverished teenagers like Kandea and Tetsuo are sent to trade schools meant to pipeline them directly into the workforce rather than provide a holistic education. In our current day, where authoritarian leaders are taking over governments like the United States, the failures of Neo-Tokyo are on display on a daily basis. The environment, the working class, the young–all are turned into gristle for the mills of these elderly leaders who merely seek to further their own hegemonic power. Otomo looks at this dichotomy and depicts it through the lens of a sci-fi action epic–simultaneously crafting a thrilling action story that also grapples with these anti-authortarian themes and ideas.

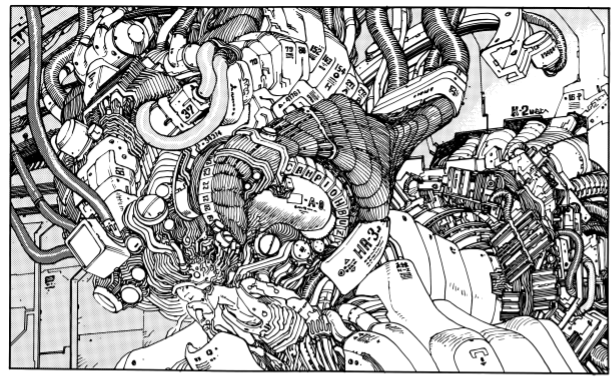

Also simultaneously and, somewhat unfortunately, the manga carries a visual fetishization of the very military power and destruction it attempts to criticize. In Steamboy, there’s this egregious credit sequence where, after two hours of blunt themes related to anti-industrialization, we see the protagonist and his friends build new and even cooler steampunk tech. It’s an ending that left a sour taste in my mouth for how it seemingly lionizes the technology it seemed to be criticizing. Akira falls into many of the same traps. While the dialogue and plot may be critical of this hungry capitalist desire for increased technological power, the visuals of the manga lavish and pan over said technology and the destruction it causes. Bodies gunned down by flying machines are lavishly drawn in Otomo’s hyperdetailed style; solar laser satellites and their destructive impact on the earth are lovingly depicted in two page spreads.

There’s a contradiction here between the themes and visuals that is hard to parse at times. In its conclusion in particular, there isn’t really much of a viable alternative presented to this lust for power exemplified by the military and authority figures within the text. There is not ever a vision of a peaceful alternative presented. In Akira, the solution to combating the violence of the military and of authoritarian figures is violence wielded by the disenfranchised. Which, to be clear, is not an unjustified conclusion to come to. However, when no alternative is brought to the table after the violence is wielded, it strikes me as not particularly well thought out. One could argue that maybe the psychic Miyako’s society, which takes in the sick and dying to care for them, is a potential alternative to the other antagonist forces presented within the text. However, with the almost cult-like reverence shown to her by her followers, it’s hard to defend this interpretation wholeheartedly.

This lack of thematic clarity is not helped by the cast of characters Otomo creates, each of whom can at times feel more like pawns in the plot and action than fully realized people. In fact, if I had one major complaint in terms of writing, it would be that characters throughout Akira remain relatively flat in terms of motivations and drives. For example, the protagonist Kaneda doesn’t change much throughout the story. One could argue that maybe he comes to have a more nuanced, less sexualized view of Kei near the end of the series, or maybe that he comes to empathize more with Tetsuo and his inner turmoil. Overall though, Kaneda starts as a hot headed natural leader willing to do anything it takes to survive and ends the manga much the same.

The character who arguably goes through the most evolution throughout the text is Tetsuo, but I would still argue that this is less of an arc and more of a layering of nuance that gives him a tragic edge as an antagonist. At the beginning, Tetsuo’s drive for drugs and more psychic power is not particularly well explained to the reader. In fact, another general weakness I’d argue the manga has as a whole is its stubbornness in holding back key character information for far too long. It isn’t until the climax of volume four that we get a clear idea of Tetsuo’s backstory and inferiority complex in relation to Kaneda. Considering Kaneda and Tetsuo’s rocky friendship is a key conflict throughout much of the manga, it seems like the backstory of their relationship should’ve been more than merely implied in the first half of this story. Akira certainly has the page count to spread this character backstory more evenly throughout its six volumes, but more often than not Otomo is busier guiding characters from one set piece to the next, leaving little room to delve into their psychological or emotional sides.

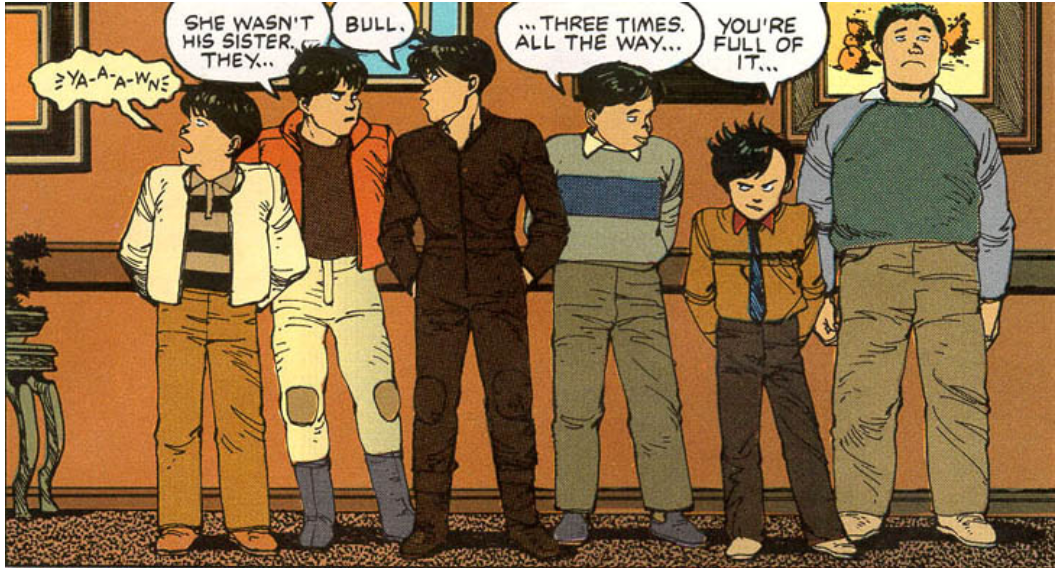

However, it's impossible to claim that these characters aren’t likable or memorable due to Otomo’s incredible skill as a character designer. I appreciate Otomo’s variation in height, visible age, and body type with the cast. There’s big visible differences between the towering, bulky stature of the Colonel and the appropriately stout, rat-like qualities of Nezu. This variety does apply more to the male characters than the women of the cast, but even there you have characters like Chiyoko–a brick house who by no means fits the typical boy’s manga ideal of feminine beauty, but who nonetheless commands reader’s respect with her imposing stature and important role as the weapons master in Kei and Ryusaku’s resistance group.

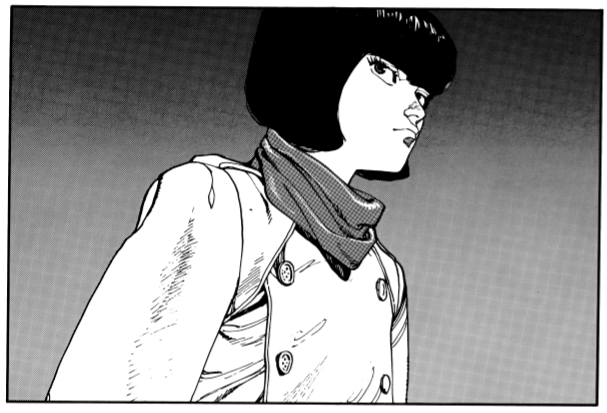

Kei in Vol 1 vs Vol. 5 (Vol. 1, Page 41 & Vol. 5, Page 21)

In general, there’s both positive and negative sides of the portrayal of Akira’s female characters. While I generally appreciate that characters such as Kei, Chiyoko, and Miyako get to be active agents who play pivotal roles in action sequences, their roles in the story tend to be more limited overall than their male counterparts. Kei is the ostensible female protagonist in the story, but she in general is more often made into a pawn for other characters due to her status as a psychic medium who merely channels the powers and will of the psychic children and Miyako. Also, due to her nature as a love interest for Kaneda, her appearance throughout the manga gets softened over the course of its serialization. There’s a big difference between her fuck-ass bob in volume one and her more feminine look in the final volumes.

None get the short end of the stick as much as Kaori though. In general, the most misogynistic, or at the very least gratuitous, depictions of violence toward women in the text find themselves in the back half of the series. Kaori, a refugee of the destroyed Neo-Tokyo, is first introduced in volume four as a character set to die at the hands of a psychic orgy held by Tetsuo, the now shadow ruler of the Great Tokyo Empire that has popped up in the wake of Akira’s second bomb. She escapes death at the hands of Tetsuo’s psychic pills by not taking them and quickly becomes a maternal figure for Tetsuo and Akira. I appreciate that Otomo is clearly painting Kaori as a desperate individual forced into this role by the destruction of the setting around her, but her status as a maternal figure for Tetsuo and Akira is never really questioned or critiqued by the text itself. In the end, Kaori is even willing to die in the process of trying to warn Tetsuo about a potential coup in the Empire, despite him currently being mutated by his psychic powers into an unrecognizable blob of flesh and machinery. Maybe this could have worked if she had been given more interiority as a character, but alas, like many characters in Akira, she feels more like a pawn than a fully fleshed out individual.

With all of these criticisms, this may make Akira sound like a shoddily produced work, but I have to switch gears and start giving Katsuhiro Otomo his due praise. In terms of action, Otomo’s skill as a comics artist is undeniable. I already praised his memorable character designs, but his work in paneling, pacing, and tension building deserve equal focus. Something I came to notice throughout my re-read of Akira is Otomo’s tendency to establish multiple groups of characters that usually share some kind of ultimate goal. However, while these groups may all be vying for the same thing, their motives tend to clash, resulting in escalating conflicts and tension as all of these individuals collide in a central location for a climatic action sequence.

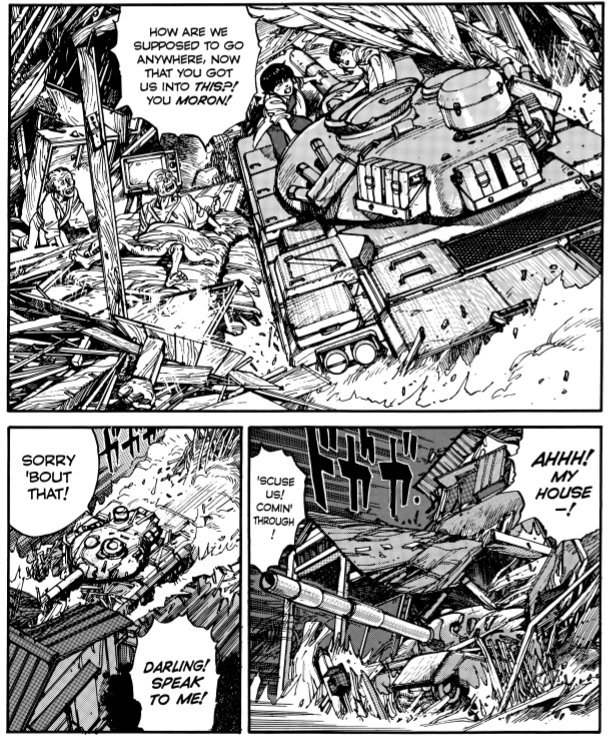

My favorite moment of this occurs in volume three, which is all about the Colonel, Nezu, and the remaining dissidents of Kei and Ryusakui’s resistance group all vying to capture the titular psychic prodigy Akira. The interweaving of these factions and the escalation of their conflict from inter-group disputes and squabbles to assassination attempts and a full on tank fight in civilian territory is truly captivating. The intercutting of these conflicts reminded me a lot of the masterful work George Miller did for the 2015 film Mad Max: Fury Road. There’s a constant sense of forward momentum and chaos, but on the page it's all perfectly legible and totally exhilarating. The paneling is buttery smooth– I can’t recall a moment throughout the entire series where Otomo’s layouts were ever confusing or hard to parse. The direction of action is always clearly guiding the reader’s eye from moment to moment and the scale and page count at which Otomo is able to maintain this sense of building tension and pacing is impressive. Of course, I would be remiss not to shout out some of the assistants that contributed to this project, including future anime auteur Satoshi Kon, who undoubtedly helped this series keep up its insane level of quality over the course of its bi-weekly schedule across eight years of serialization.

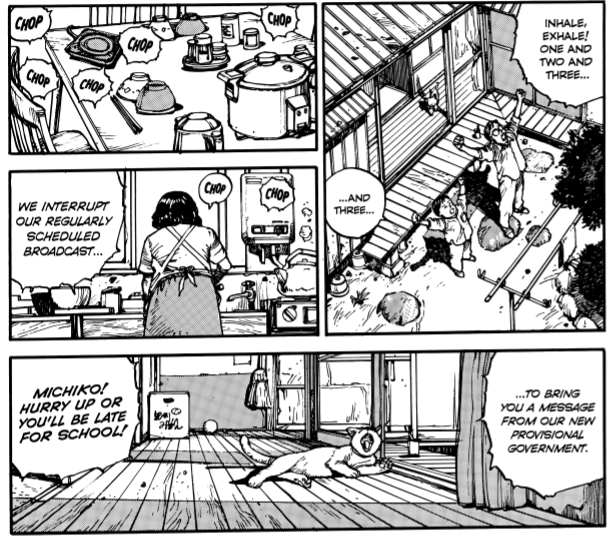

Plus, while I may be critical of the way Otomo may lavish in the destruction and military tech on the page, there are exceptional moments of humanity he injects throughout the manga. At its best, the manga does a good job at emphasizing the immense human toll of this avoidable conflict, such as in aforementioned volume three where we cut from Akira starting a new psychic bomb to a montage of average civilians getting ready for school and work. It’s a chilling calm before the storm moment as we watch these normal families converse while on their TVs the announcement of martial law is rebroadcast. It captures the mundane reality of the everyday people caught in the middle of these military conflicts. Even as the government is couped by the military and citizens are ordered to remain indoors, these children get up and have breakfast. It makes the impending destruction caused by Akira all the more impactful and haunting as a result.

This sense of tragic loss is something that carries over into the finale of Akira, which I have mixed feelings on. It’s a land of contrasts in terms of containing both some of the manga’s best character and thematic moments, but also some of its most incoherent decisions and political ideas. There’s this stunning moment in the finale where Kaneda is swept up into Tetsuo and the other psychic children’s dying memories. He’s forced to relive his first meeting with Tetsuo and additionally is told by Kiyoko a sort of contrasting view about the nature of the psychic children within the story. Throughout the rest of the manga, controlling and getting rid of Akira or Tetsuo have been primary goals. In some ways, one could interpret the manga as being against the very existence of these psychic children.

However, in these final moments with them, the text complicates this un-nuanced view and reminds us that, like many of the characters in this text, the psychic children were swept up by the whims of hegemonic military powers outside of their control. In this sequence, Kiyoko presents a utopian idea of the psychic children representing the next stage of humanity–one that can communicate with each other without words and without having to always be face to face. In a story where much of the conflict is driven by misunderstanding, or characters failing to cross paths with each other, this idea is a breath of fresh air. Still, Kiyoko acknowledges that in the hands of the military, these psychic children could be nothing more than experimental weapons fed “such harsh fertilizer" and forced to grow too fast, too quickly.

I believe we are supposed to carry this feeling of utopian idealism into the remainder of the ending, which focuses on the reveal of Kaneda, Kei, and the others having reclaimed the Great Tokyo Empire for themselves. Rather than accept United Nations intervention, Kaneda merely tells them they’ll accept food and medical aid, but continue as a sovereign nation. A new Great Tokyo Empire led by cool bikers instead of authoritarian egomaniacs like before… or at least, that’s the positive interpretation.

There’s a kind of interesting ambiguity to these final pages that I find compelling yet deeply frustrating. On one hand, I like the anti-interventionist angle, but I find it troubling that Kaneda would attempt to reclaim this sovereign nation idea. Being called the Great Tokyo Empire implies an inherently imperialist project… I mean, the word empire is literally in the name. Yet, I think Otomo wants us to have a feeling of pride in these final moments; a sense of satisfaction that these young characters have escaped the hegemony that has oppressed them throughout the rest of the story. Certainly, I can get down with the latter part, but it also strikes me as painfully naive to imagine a gang of bike riders could manage to pull together any modicum of a functioning society in the rubble of Neo-Tokyo. The positive interpretation is a kind of anarchism free from the capitalist world order. The negative interpretation is a kind of libertarian delusion of a society somehow functioning without any kind of coherent community cooperation or oversight, just cool biker dudes and their girlfriends riding off into the ruined sunset. It’s a beautiful image, but one with fraught somewhat reactionary implications. Maybe between this and Steamboy, it’s clear Otomo just isn’t the best at writing endings. Still, the thrills of the journeys toward said endings are hard to deny.

Throughout the process of re-reading Akira and discovering more about its production and international publication history, I was struck by how oddly difficult it is to read Akira in its original format in the United States. There have been three versions of Akira published in the US and all of them have been fraught in their own unique ways. The first edition, as mentioned before, was digitally colored by Steve Oliff, and while his work in digital coloring was revolutionary for the medium, it’s hard to look back on this decision without side-eying the choice. It was one that probably felt necessary since, at the time, European and American comics were largely printed in color. Additionally, as was common for this era, the comic was flipped from its original right to left reading orientation to the Western left to right orientation. This meant Otomo had to often redraw backgrounds and word bubbles in order to make this English edition maintain the same readability as the original Japanese version. I guess there’s something admirable about these attempts at localization, but from a modern day perspective where flipped editions of manga are a frowned upon rarity, it’s odd that such great lengths were gone to by the original artist to fundamentally transform the original reading experience of the work. As such, it is unsurprising that this color version of Akira has never been fully reprinted in the US (though it is still quite easy to access online as I discovered in the process of preparing for this post).

The second edition from Dark Horse in the 2000’s was a marked improvement over these initial releases from Epic/Marvel. They kept the original black and white art and formatting of the six Japanese tankoban/collected print edition releases. These English releases were still flipped to left to right though, which makes it all the more frustrating that these editions have been used as the basis for Kodansha USA’s modern day paperback editions of the manga. To this day, the cheapest, most accessible form of the comic available to the average US reader will be these flipped paperback versions.

The third and final edition, and undeniably the most comprehensive and faithful release in the US to date, is Kodansha USA’s 35th anniversary boxset release. These not only keep the original manga’s right to left orientation, but even go so far as to leave the original hand drawn sound effects unaltered, instead translating them via glossary or on-page annotations. This is the edition I purchased several years ago and used for this particular re-read. In fact, it was the status of this being the only right to left version available in the US that pushed me to go through with this purchase. As mentioned before, the cheapest and most accessible version of this is still the left to right paperback edition of the manga. While you will usually also find the 35th anniversary boxset in stores alongside these older releases, the hefty price tag on the boxset does make it a less accessible option for new readers.

I find this… frustrating. You could get lucky and these hardcover anniversary editions might be available at your local library, but again I imagine your library is more likely to have the older left to right paperbacks than these newer bundled together editions. For a comic that is so influential, the difficulty of accessing a cheap, faithful rendition of it is odd to say the least. Shouldn’t a text that is still visually referenced in modern films be a tad easier to read its original formatting? And additionally, why has no digital edition of the manga been made available in the US either?

Whether or not you end up finding Akira to be an exhilarating action thrill-ride worthy of its reputation, or end up being off put by its more politically fraught or crusty elements, I believe Akira is a historically important manga that should be easy to purchase in its original format. The fact it isn’t points to a failure of Kodansha, which is a failure that also extends to their seeming inability to publish Otomo’s other work in the United States as well. To date, the only other manga written and drawn by Otomo published in English have been the short story collection Memories, which was published exclusively in the UK and is now out of print, and Dark Horse’s release of Domu, a kind of spiritual predecessor to Akira that is now also out of print. Kodansha in Japan has been publishing lavish editions of Otomo’s entire catalogue called Otomo Complete Works, a series of releases that is still ongoing. Maybe Kodansha USA is waiting for this series to be complete in its entirety before releasing any English editions, maybe they’re afraid the audience for Otomo works besides Akira isn’t large enough. Either way, I think they are severely underestimating the financial viability of the work of an artist and series that is wildly popular in the United States even today. That 35th anniversary edition has been reprinted at least once to my knowledge, so I’m not sure what Kodansha USA’s reasoning on these topics could possibly be.

There’s honestly so much more about the original Akira manga that could be discussed here. Whether that be Otomo’s excellent use of body horror in the latter half of the manga, or the year long hiatus that occurred during the manga’s initial publication, but I think these interesting aesthetic strengths and production history quirks are best saved for future discussion on the manga’s equally popular and seminal animated adaptation. Yes, I will be discussing the anime adaptation in a future post. No, I hope it isn’t as bloated as this one ended up being. Until then, I hope you got something interesting out of my ramblings here. As always, thanks for reading.