Revisiting Akira - Part 2: The Anime

A catalogue of thoughts accumulated while rereading and rewatching Akira...

Like with my previous post, to begin discussing the 1988 film adaptation of Katushiro Otomo’s Akira, it’s important to include some context about its production. Akira (1988) is an interesting adaptation in many ways since it presumes to tell a complete, albeit heavily truncated version of the manga’s story, but was produced before the actual serialization of the manga concluded. In fact, the manga’s serialization was put on hold in 1987 specifically due to writer and artist Katsuhiro Otomo’s involvement with the film production. Akira is not typical for anime adaptations in that Otomo himself handled both directing the film and co-wrote its script with writer Izo Hashimoto. As outlined in a video interview included on the US laserdisc release of Akira, Otomo specifically requested full creative control due to his prior experience working on the anime production for the film Harmeggedon. The result is the rare manga adaptation where the original creator was able to fully supervise and adapt their own story.

In the Akira Club artbook that comes with the 35th anniversary edition boxset in the United States, you can actually read Otomo’s author comments that were written for each chapter during the manga’s serialization (alongside the original chapter artwork excised from the volume/tankoban releases). This includes the comment Otomo wrote about the manga’s hiatus. The message, published with chapter 88 in the April 20th, 1987 issue of Young Magazine, stated: “I’ll be taking about two months off in order to begin preparations for the animated version of Akira. Thank you.” Instead, the hiatus lasted for over a year with the manga returning in November 1988.

Still, I imagine it was hard to complain too much about the hiatus since it resulted in one of the most influential and acclaimed anime films ever made. In many ways, Akira (1988) is even more influential than its manga counterpart. As mentioned in the prior post, it is still visually referenced in modern films, from Jordan Peele’s Nope, to 2024’s Sonic the Hedgehog 3 having Shadow perform Kaneda’s iconic motorcycle slide. Additionally, the film has rarely been out of print in the United States, even as it's been passed around from licensor to licensor over the several decades after its initial international release.

In fact, the film is so influential and revered that myths have popped over the years about its production history. Akira (1988) is often touted as one of the most expensive anime productions up to that point in the 1980’s, which was disputed in a 2020 article written by Daryl Harding for Crunchyroll News. A producer on the film, Junya Suzuki, has stated on Twitter that he doesn’t understand where rumors of the film having a “1 billion yen budget” came from. He eventually provided quotes to prove the film’s original budget was around 500 million yen, a number in line with the budgets of contemporary anime films like Hayao Miyazaki’s Castle in the Sky.

Similarly, there are misunderstandings around the quality and development of the film’s animation itself. Another common misconception online for years is that the film was animated all on 1s. For those unfamiliar with animation terminology, referring to an animation cut being animated on 1s means that for standard 24 frame per second film a drawing is created for all 24 frames in a second. For those who are familiar with animation production, this is clearly an outrageous claim. All animated productions include a variety of frame counts depending on the motion being depicted in each cut. As outlined in a video essay by the Youtuber APLattanzi, while Akira does have a large amount of cuts animated on 1s, the film does have cuts animated on 3s and 2s. A whole film being animated on 1s would not only be impractical, but also probably not even look good. Having every cut be animated on 1s would likely give everything an uncanny, smooth quality. Part of animation as a medium is using a variety of frame counts to highlight key moments of action and character movement. Still, that mythification surrounding the film and its production speaks toward the film’s fandom, as well as the general quality of its production. To this day, people still cite it as a landmark visual work, and rightfully so.

Before fully diving into that though, there is something that I failed to discuss in my previous post on the manga that I would be remiss to not mention in my general coverage of Akira. Something that I somehow managed to avoid in the prior post are the obvious historical influences on Akira’s imagery of war and destruction. Katsuhiro Otomo was a child during the conclusion of World War II and, like all Japanese artists of his generation, was likely influenced by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of the Pacific War. Like Godzilla and other sci-fi works from Japan, the imagery of the Akira bomb can be directly paralleled to this horrendous act of violence inflicted on innocent Japanese civilians. The commentary in Akira on military authoritarianism can be seen as a reaction to the memories and remnants of Imperial Japan and I feel silly for not bringing up these points in my previous post.

Anyways, part of choosing to cover the film after the manga was an attempt to approach the film from a different angle. When I first experienced Akira, the film was my first touchpoint for this story, which is probably the case for a majority of Western fans. As such, I sought out the manga in an attempt to better understand the film and didn’t really ever come back to it to view it as an adaptation of that source material. Going into these rewatches of the film (because I ended up watching it twice for this post), I was concerned with analyzing it through said adaptive lens.

The results were… interesting. The common online discussions surrounding Akira (1988) is that it is a cramped and confusing adaptation. This was admittedly the impression I had of it as a first time viewer who felt there were many missing pieces from the film on the first watch. Coming at it from the opposite angle though, I actually found there are many strengths to the film as an adaptation and came away impressed with Katsuhiro Otomo’s ability to translate the visuals and story of the manga into a two hour film production.

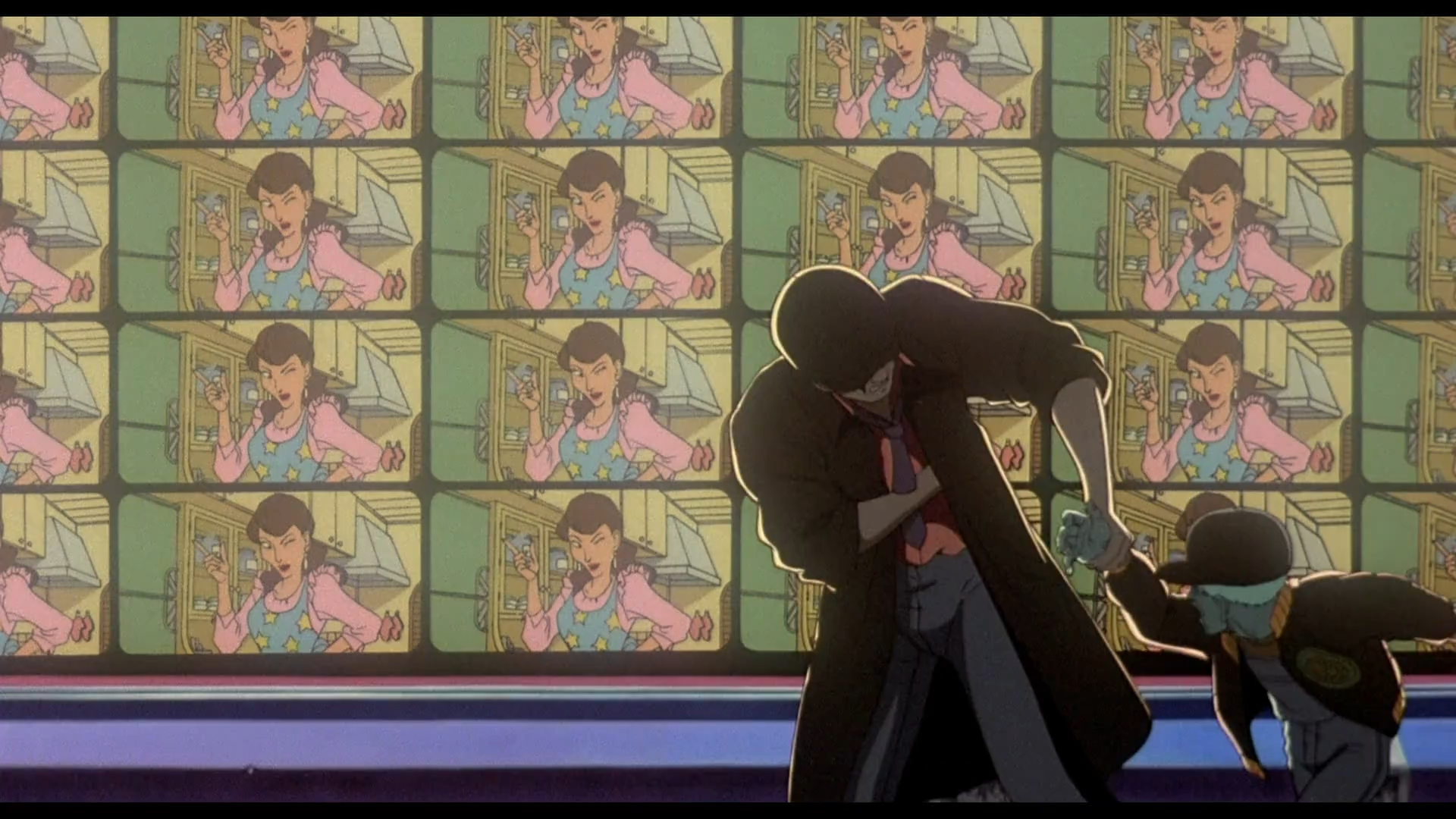

Neo-Tokyo Imagery from Akira (1988)

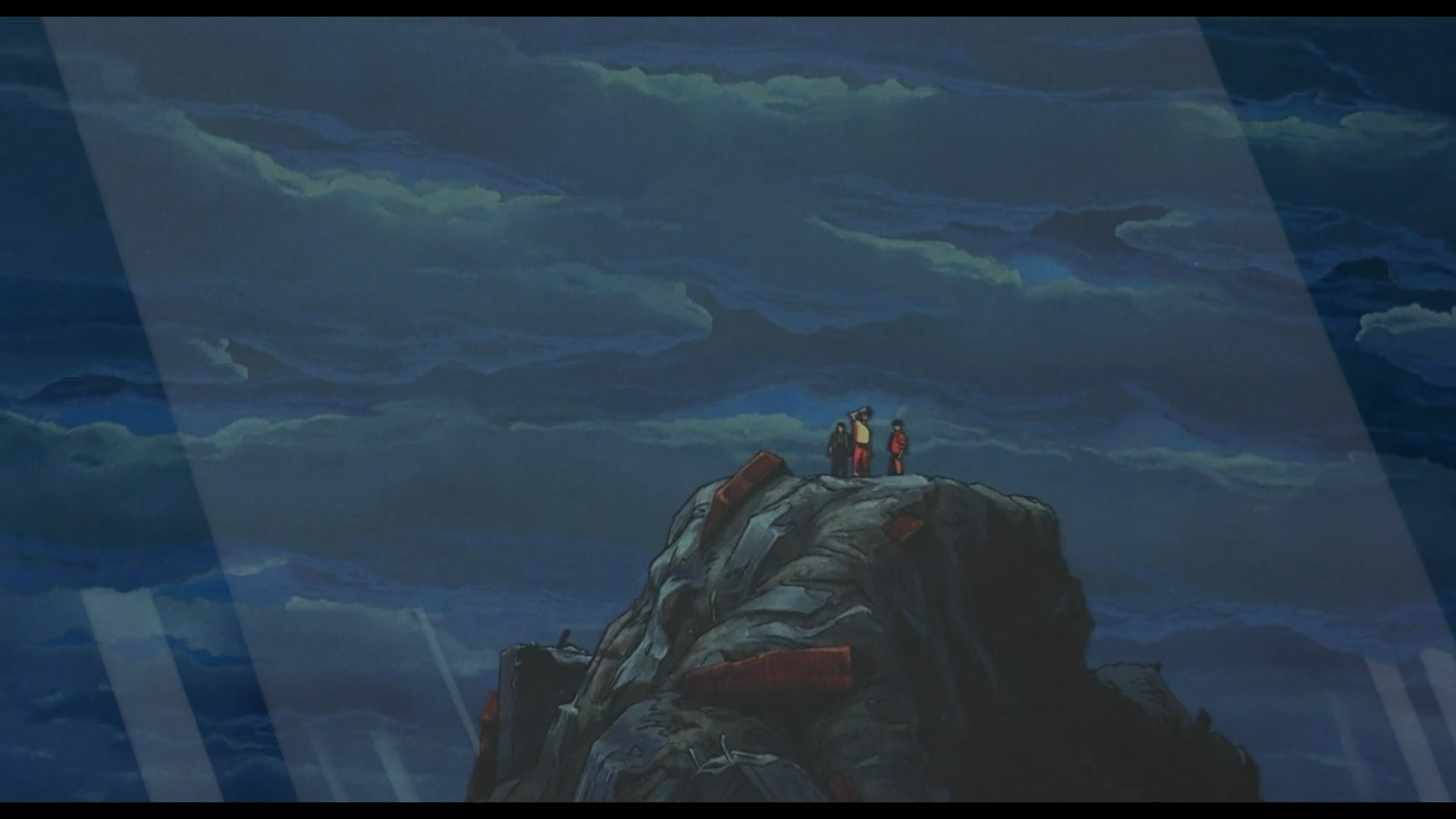

Of course, the main point of praise for this film is the aforementioned astounding visuals, which hold up even today. Akira is an example of the heights the cel animation era could reach–lush, detailed, and textured in a way that modern digital productions have only just begun to match in some ways. The color pages of the Akira manga were actually quite uneven in my opinion, so I was surprised to learn in the laserdisc interview that the color palette of the film was based in part on those spreads. The film version of Neo-Tokyo is beautifully translated into animation–filled with garish neon lights and disheveled urban streets, the backgrounds a treasure trove of screens, wandering people, storefronts, and other minute details. There’s something magical about seeing the crowds and clutter of the setting in the manga portrayed in motion. The cyberpunk influences of films like Blade Runner can clearly be felt on the production, but Otomo coming from an actual Asian country means he merely heightens and exaggerates the existing metropolis of 1980’s Tokyo, lending the cyberpunk city an authenticity and nuance not found in Blade Runner’s orientalist stereotypes.

Similarly, the wonderful character design work from Otomo’s manga is captured expertly by the skill of animation director and adaptive character designer Takashi Nakamura. In fact, Nakamura was one of the reasons I was excited to rewatch this film due to his directorial work on the highly underrated 2002 anime film A Tree of Palme (a personal favorite of mine). Nakamura’s adaptive designs capture all the charm and detail of Otomo’s original manga art. In fact, the level of detail kept in the film production is quite astounding–the production of this film must have been laborious considering there are not many corners cut. Maybe you could argue Nakamura’s interpretations of the characters have slightly more simplified and rounded eye shapes, but costuming and proportions remain quite realistic and detailed.

This makes all the action spectacle in this movie all the more impressive. Otomo’s skill in paneling translates wonderfully into the storyboards–action is clear cut and fluid, made doubly impressive by the realism of the movement. This realism is enhanced by certain creative choices made, such as the choice to use pre-scored dialogue. For those not aware, most anime productions, unlike Western animation, record dialogue typically after storyboards or animation is already complete. This means that lip flaps are generally not synced with the voice lines in anime. Akira is a rare exception to this–a fact that only adds to the level of detail present in the production.

Tetsuo's Transformation

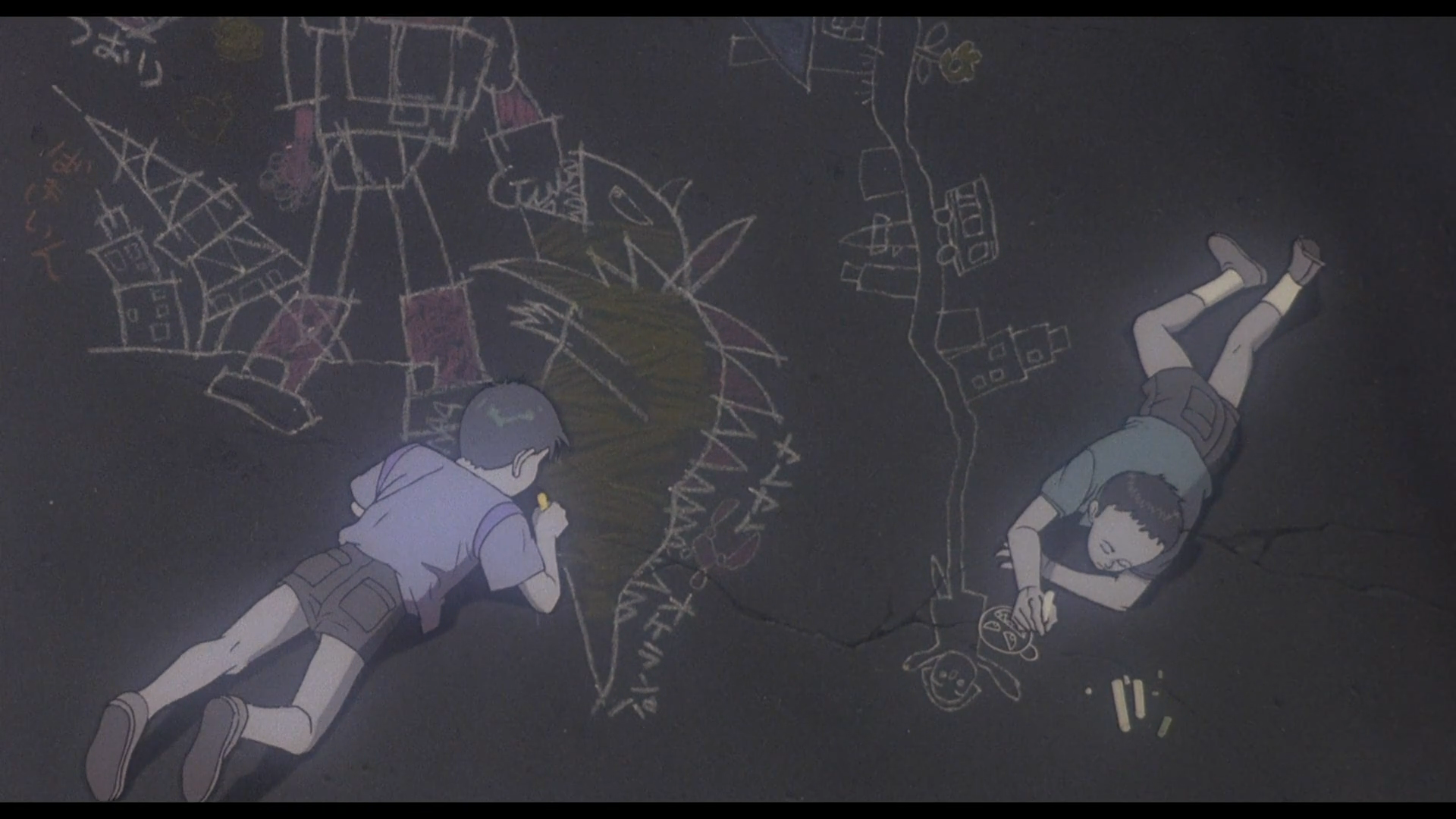

However, more impressive than the action to me is the body horror of the film’s climax. At the time of the manga’s hiatus, readers had only caught a glimpse of the transformation caused by Tetsuo losing control of his ever growing psychic abilities. As such, the film version of Akira serves as the visual basis for the future chapters of the manga, depicting Tetsuo’s morphing into a blob of flesh and machinery. The cuts of Tetsuo in these climatic moments of the film are pure body horror. There are at once primordial and futuristic: Tetsuo’s metal arm spreading out like computer wires, while his flesh ultimately transforms into the visage of a newborn infant. It works wonderfully with the motifs of early childhood that are present throughout the rest of the work with the appearances of the fellow psychic subjects and their often childlike approaches to antagonizing Tetsuo earlier in the film with stuffed animals and milk. All of this is matched wonderfully sonically–the psychic children like Masaru and Kiyoko have these eerie flat, young voices that contrast with their aged bodies. Meanwhile, the soundtrack, composed by the collective Geinoh Yamashirogumi, gives the action and horror a thumping drum backing mixed with Bulgarian style harmonies for pulse-quickening and unsettling effects.

Jumping off the prior mention of the film’s climax informing much of the manga version of Akira’s ending, I think many of the strengths and weaknesses of the film adaptation can be pinpointed to that interplay of what material Katsuhiro Otomo had and had not already written in the manga. The strongest segments of the film version from a script standpoint are easily in the first two thirds, which largely adapt material from the first three volumes. During the film’s production, these segments had been published for a while and edited by Otomo for the tankoban/collected volume releases. As such, Otomo’s able to find clever ways to streamline this existing material for a two hour film version.

The opening is the most effective in this regard. I love the choice to juxtapose Nezu’s rebel group escorting the psychic child Takashi through the streets of Neo-Tokyo with an ongoing student protest. The manga certainly portrays the chaos of Neo-Tokyo, but it focuses so much on the Colonel and Nezu when it comes to politics that it fails to give a clear vision of the city’s ground level civilians. By simply adding this student protest to the beginning of the film, it instantly establishes the authoritarian nature of this society as the viewer witnesses these protesters being pushed back with tear gas by the police. In general, the efficiency at which the first hour of this film establishes factions and groups within Neo-Tokyo is impressive. By the time Kaneda, Kei, and the other rebels are invading the military hospital housing Tetsuo and the other psychic children, we have a clear vision of the conflicting religious, governmental, and military groups within the city.

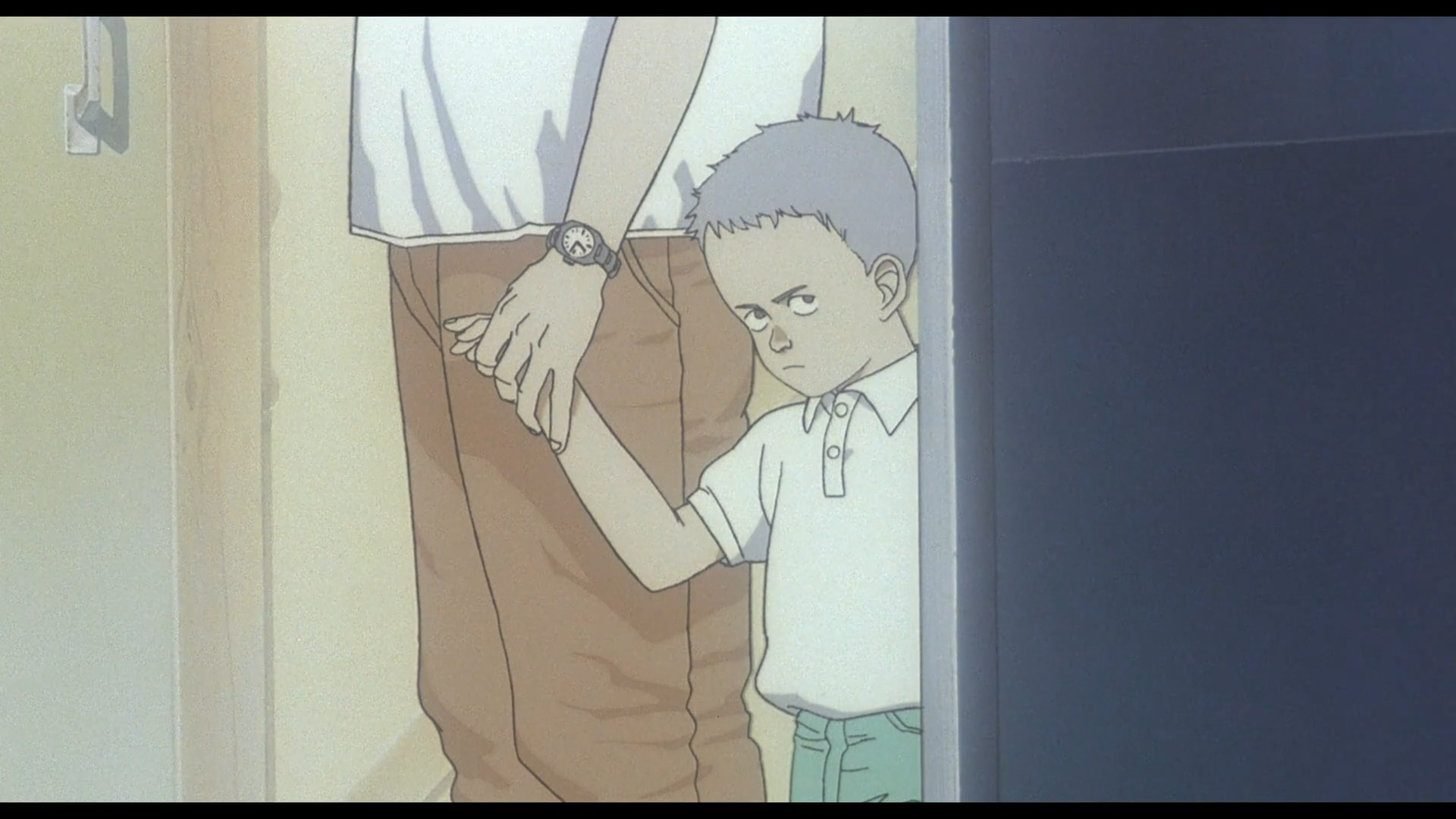

Tetsuo's Childhood with Kaneda

My favorite adaptation changes though revolve around the relationship between Tetsuo and Kaneda. As mentioned in my prior post, the manga doesn’t start exploring the backstory of their dynamic and relationship until the end of volume 4. Because much of this material was already written by the time of the film production though, Otomo is able to draw upon it and better establish their connection and conflict at earlier points in the story. This makes Tetsuo not only a much more sympathetic character, but also makes Kaneda’s drive to find Tetsuo and stop him more emotionally complex than it appears oftentimes in the manga. In that version, it often seems like the major catalyst for their conflict is more Yamagata’s death than any prior bubbling resentment between Kaneda and Tetsuo.

These strengths make the areas where the script fumbles or relies on clunky exposition all the more disappointing; and it’s telling that many of these moments correspond with themes and scenes that had either not been drawn or were still being written in the manga version. One egregious example is Kei’s monologue to Kaneda while they are trapped in a holding cell. This moment is clearly meant to explain the nature of the psychic children’s powers, but while the manga has three volumes in the second half to expand upon this idea of the children harnessing the underlying energy that powers all living things, Kei has five minutes to clunkily exposit these complex theoretical sci-fi concepts to the viewer. It’s easily the clunkiest moment of exposition in the film.

Similarly, the entire climax with Tetsuo’s transformation and the psychic children setting off the new Akira bomb feels like a rough draft of what the manga would ultimately end up executing. Which makes sense! In terms of the production timeline of both versions, the film was the one that came first in this regard. Unlike the beginning of the story where Otomo had material to adapt, Otomo only had his rough outline of the story to work off of for this finale. Considering he mentions in the laserdisc interview that even with this outline there was much additional development during the serialization of the manga (not surprising as that is common with most series existing on a tight bi-weekly schedule), it’s not exactly shocking that the ending of the film comes across as less tightly structured than its first two acts.

Additionally, while I generally respect many of the choices made in terms of characters being cut or shifted around in the adaptation, many of the female characters end up somehow becoming more passive and vestigial in the film version. Compared to her manga counterpart, Kei is somehow even more passive an agent. She screams and seems shocked upon killing someone in the sewers, whereas Kei early on in the manga struck me as a confident and controlled rebel operative. Kaori gets the worst treatment here though. She’s rewritten to be present in the story earlier on as Tetsuo’s girlfriend for reasons that I frankly don’t understand. In the manga, her desperation and attachment to Tetsuo is a product of her existing in a post-disaster Neo-Tokyo. Meanwhile, in this film incarnation, she is merely a damsel to get beat up and tossed around for audience pathos. This is certainly true of her manga counterpart as well, but you can at least argue for there being thematic and worldbuilding purposes for her character in that version of the text. Here, her inclusion and death at the end of the film somehow come across as more pointless and grim than the original text. A depressing feat all things considered.

There are of course even more things I could nitpick and complain about that carry over from the manga: my prior complaints about relatively static characters and thematic incoherency surrounding the fetishization of military destruction still stand for the film adaptation. However, while these critiques can certainly be made of the film version, I must admit that there is a certain visual impact to Akira (1988) that I believe contributes to the film’s ongoing legacy. What Akira lacks in deep thematic consideration it makes up for in the power of its imagery. It’s hard not to be awed by Otomo’s vision of cyberpunk dystopia and see an eerie prescience in it. Going back to the student protest in the film version, that imagery of the protesters being pushed back and engulfed in tear gas is not dissimilar to imagery we see in modern protest movements like Black Lives Matter. As authoritarianism becomes more and more an overbearing force in countries around the world, but especially in Imperial Core nations like the United States, Akira’s vision of a 2019 future torn apart by the hubris of its rich military and political leaders repeating the mistakes of the past grows more potent, not less.

That feeling it captures is what makes this film engaging and relevant even today. My second rewatch of this film was with my roommates, two of whom had neither read or watched Akira. Seeing them struck with awe at the detailed action animation and horror at Tetsuo’s transformation were truly enjoyable experiences. There is an intensity and verve to Otomo’s work in film and manga that seems to remain eternal. For that alone, Akira is worth experiencing, warts and all, for what it can teach us about how far we’ve come and what has yet to change.

As always, thanks for reading.