Whisper of the Heart: Urban Life & Creative Awakening

It’s odd to claim that a film from one of the most critically acclaimed animation studios in the world is “underrated," but...

It’s odd to claim that a film from one of the most critically acclaimed animation studios in the world is “underrated,” but out of the twenty-plus feature films studio Ghibli has produced, Whisper of the Heart is one I wish more people would talk about and watch. Every Ghibli aficionado probably has one of those, but I argue in favor of Whisper of the Heart due to its particular unique qualities. There is of course its impact on Ghibli iconography–one could argue the feline Baron von Humbert Jechingen is one of Ghibli’s core merchandisable characters. It's also the only Ghibli film with a sequel of sorts in the form of The Cat Returns, which brings back the Baron for a silly, short, and sweet fantasy adventure. It also has made an impact in Lo-fi culture. The Lo-fi girl you might have seen on the popular “Beats to relax/study to” live stream is based on an image of Whisper of the Heart’s protagonist Shizuku. However, these are rather surface-level, aesthetic elements of the film, which itself is filled with so many other elements worthy of a long legacy. In fact, even bringing up the Baron and The Cat Returns is kind of a misdirect–the Baron’s presence is relatively low key in Whisper of the Heart and him being turned into a mascot for the company strikes me as one of the odder things about this movie and its history.

Whisper of the Heart, in spite of what the fantastical GKids blu-ray box art might trick you into thinking, is in actuality a low key, romantic coming-of-age film. It follows the story of Shizuku, a girl about to graduate junior high in Tokyo who starts the film listlessly reading her way through hot summer days in the city. The film can be split into two halves. The first follows Shizuku as she tries to uncover the mystery of “Seiji Amasawa,” a name that somehow manages to appear on a majority of the library cards of the books she checks out from her public and school libraries. Along the way, she discovers a charming antique shop hidden in the hilly suburbs behind the public library by following a fat and wiley cat named Moon. There she makes friends with the old shopowner and discovers the iconic Baron statue. During these encounters, she continues to run into a smart aleck boy who seems to have some connection to the antique shop. In the fallout of a messy, albeit mundane love triangle between her friend Yuko, the baseball player Sugimura, and (unknowingly) herself, she returns to the antique shop and discovers the aforementioned smart aleck is not only the grandson of the shop owner, but also the ever allusive Seiji Amasawa.

It’s here we transition into the second half. During these revelations at the antique shop, Shizuku also discovers Seiji aspires to become a violin maker and hopes to take on an apprenticeship in Cremona, Italy. This of course threatens to cut off the budding romance between the two, but rather than this dampening Shizuku’s mood she ends up motivated by seeing Seiji dedicate himself fully to a craft. Based on the positive feedback received for her writing on a summer translation project of the song Country Roads, she decides to challenge herself to finish a story by the time Seiji returns from his trial run apprenticeship in Italy. The film then follows her trials and tribulations as she discovers her artistic passion with full force, realizing along the way what it means to dedicate yourself to an artistic craft and the amount of labor and studying it truly takes.

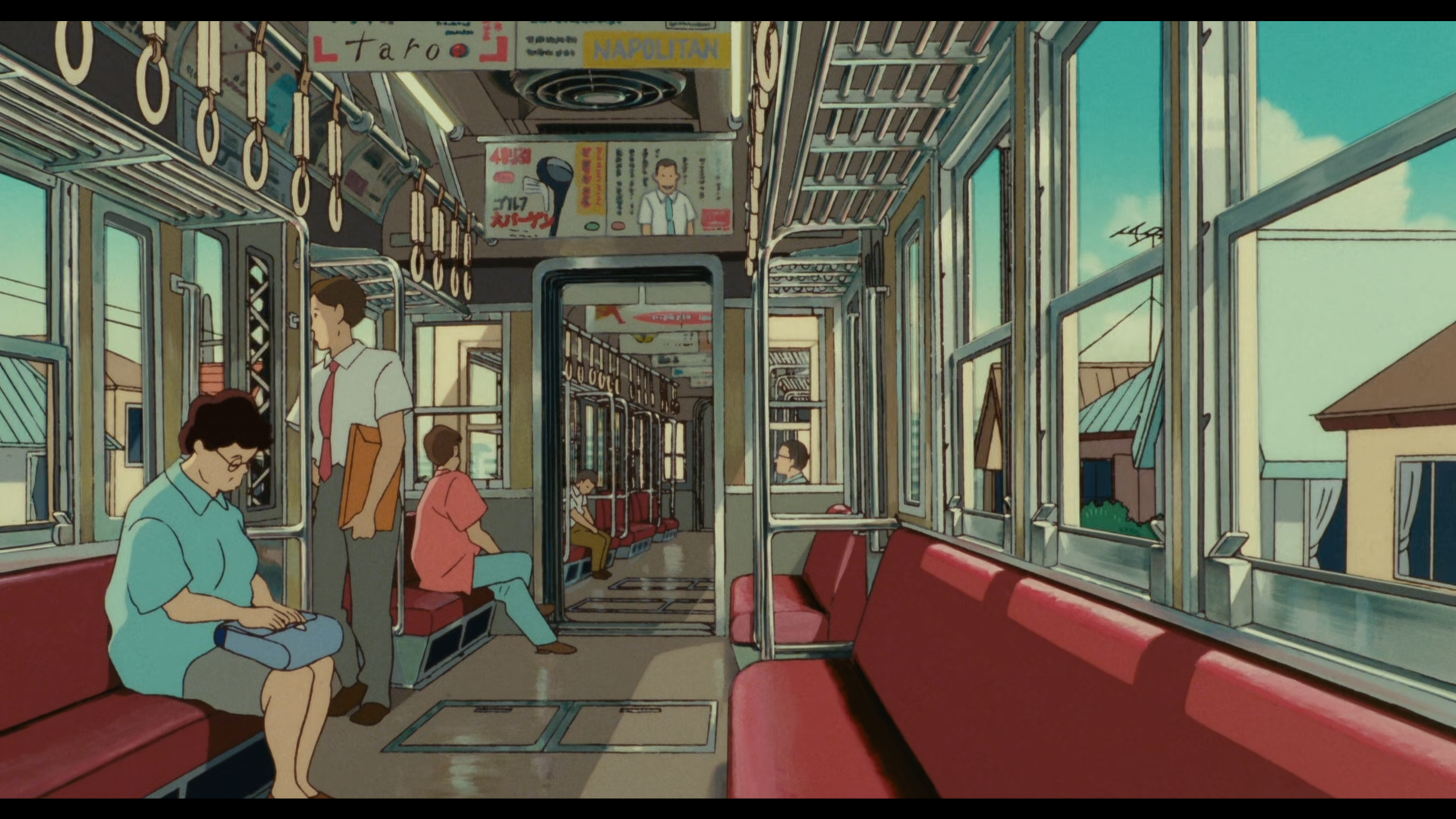

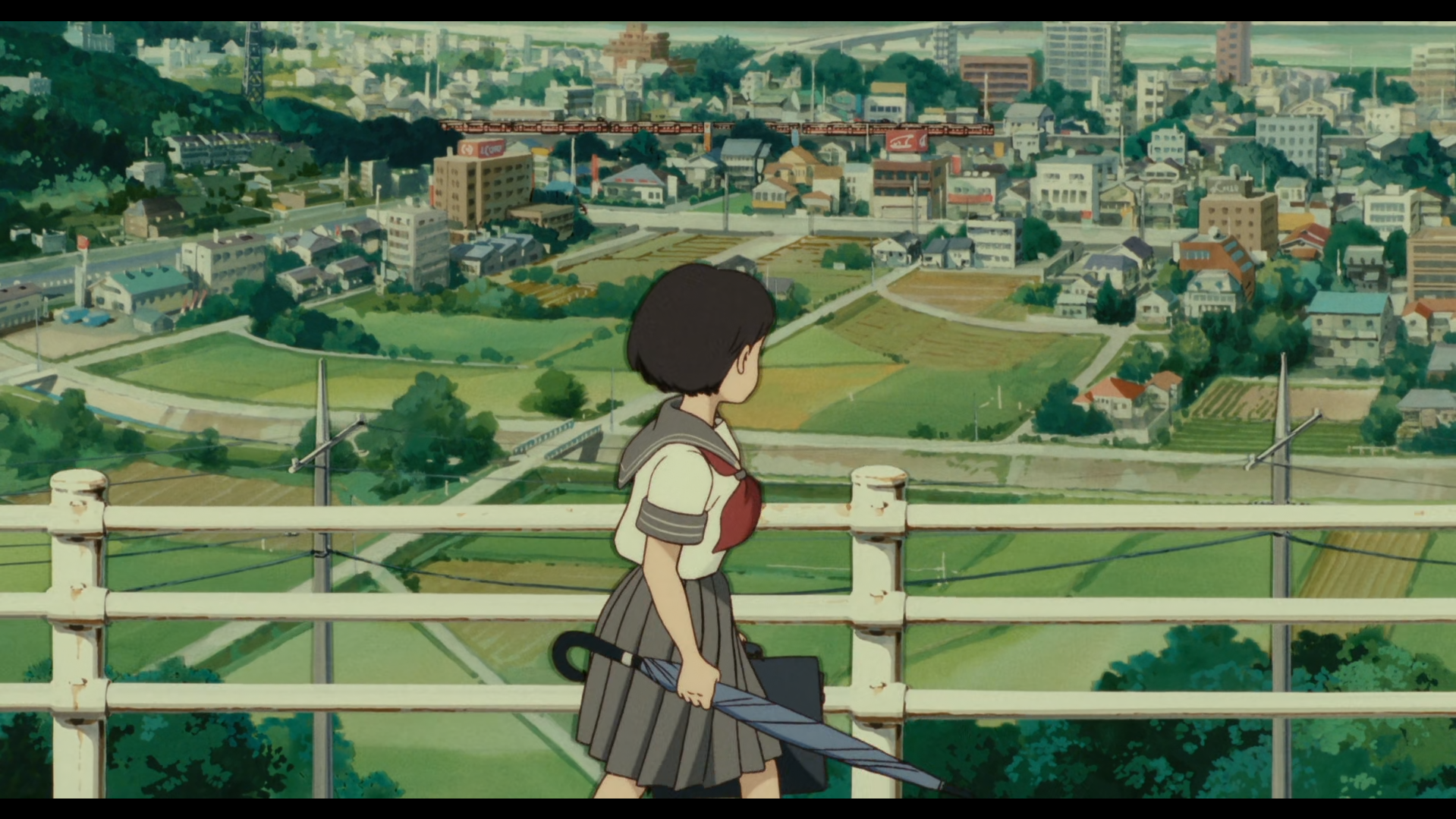

Based on that description, the film likely sounds slight, and indeed Whisper of the Heart is a slice of life film focused on depicting mundane moments of city life in 90’s era Tokyo. Unlike most other films in Ghibli’s catalogue, Whisper of the Heart is not set in either a fantastical or pastoral location. Even Ghibli films set in contemporary eras tend to place themselves predominantly in rural locations. They might start or end up in the city at some point, as is the case with Ocean Waves and When Marnie Was There, but typically it isn’t long before we end up in a smaller seaside town or something similar. Meanwhile, Whisper of the Heart wears the urban nature of its story on its sleeve. The film opens on a montage of Tokyo underscored with deliberate irony by Olivia Newton John’s cover of Country Roads. The juxtaposition between the lyrics of the song reminiscing on life in the countryside are contrasted with these lush shots of urban life–the subways and light rails, crosswalks and highways. We first are introduced to our protagonist Shizuku, not as she lets her imagination run wild in a fantasy world of her own making as depicted on the blu-ray box art, but with her exiting a convenience store after a quick grocery store run.

This central focus on and depiction of contemporary urban life is one of the reasons this film stands out so much to me among Ghibli’s catalogue. In fact, this focus on the contemporary setting is something that Hayao Miyazaki highlights in his project proposal for the film where he explains why he wants to adapt Aoi Hiiragi’s original 1989 shojo manga for the big screen:

“As the twenty-first century gradually begins to reveal its chaotic form, the structure of Japanese society has started to creak and groan. We have clearly entered an era of volatility. Yesterday's common sense and accepted theories are rapidly losing their appeal. And even if–thanks to the accumulation of material goods–today’s young people have not yet felt these waves of change, there are obvious signs everywhere of what is to come. In this new era, what sort of film should we make?”

In the proposal, Miyazaki outlines a general desire to convey a message to young people about what it means to aspire to something greater in life. He puts it rather bluntly in the following quote:

“This film will represent a type of challenge, issued by a bunch of middle-aged men who have lots of regrets about their own youth, to today's young people. It will attempt to stimulate a spiritual thirst, and convey the importance of yearning and aspiration to an audience that–just as we middle-aged men once did–tends to give up easily on the idea of the being stars of their own stories”

Furthermore, he states that Whisper of the Heart will “not try to sympathize or curry favor with young audiences and their current tastes. Nor will it question or deliberately try to raise awareness regarding the problems young people face or the circumstances in which they find themselves.”

The city as depicted in Whisper of Heart

I find this entire proposal fascinating, because at least in my estimation of the film, Whisper of the Heart is very obviously interested in lovingly depicting the life of the 90’s urban Japanese teenager. The lavishness and care given to depicting Tokyo is on the level of the studio’s past and future depictions of any pastoral setting. Director Yoshifumi Kondo really lets the viewer exist with Shizuku in these urban spaces: sitting with her on train rides, depicting the thrill and excitement as a trip to the library evolves into a cat chase through back alleys into a nice neighborhood she would have never stumbled upon otherwise. In these moments, the film captures the experience of being a pre-teen in the city–the various undiscovered neighborhoods and antique shops becoming the equivalent of a lush field of flowers or mysterious magical forest.

In fact, Kondo being the film’s director is another reason that Whisper of the Heart stands out to me amongst Ghibli’s catalogue. As one of the handful of films in their history not directed by a Miyazaki or Isao Takahata, it represents a potential turning point for where the studio could have gone creatively. Some sources even state that Hayao Miyazaki planned to retire after Princess Mononoke and let Yoshifumi Kondo take over a creative lead at the studio, though I was unable to corroborate this via an official online source. It would make sense though–Kondo was a frequent collaborator and contemporary in the industry with Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata. Kondo’s most prominent work before Whisper of the Heart were his character designs and animation direction on Takahata’s World Masterpiece Theater classic anime adaptation of Anne of Green Gables. Unfortunately though, Kondo passed away on January 21st, 1998 due to an aortic dissection attributed to overwork on the production of Princess Mononoke that had wrapped the year prior.

It’s sad that Kondo isn’t alive today, not just because of the loss of a talented artistic voice, but also because it means he is unable to provide commentary on his one major directorial work. I suspect that his vision differed from Miyazaki’s initial project proposal in some ways. Again, there’s this loving depiction of urban pre-teen life that just doesn’t seem to be a priority for Miyazaki in the initial proposal. That being said, it’s hard to imagine that if the film had been directed by Miyazaki that he wouldn’t have also luxuriated in depicting the downtime of wandering through city streets and sitting in subway cars.

What is evident in Hayao Miyazaki’s proposal though is the other central focal point of what makes Whisper of the Heart unique from a story perspective–the thematic focus on creative awakening. There’s the aforementioned quote about wanting to “convey the importance of yearning and aspiration” to a younger audience, but in describing the central conceit of the film Miyazaki also states: “At a time when most children are generally avoiding the future…our young boy [Seiji] is living purposefully, focusing far into the future. So when our young heroine encounters such a boy, what happens?” Core to Whisper of the Heart is this transition from pre-teen aimlessness to discovering an artistic passion. Shizuku at the start of the film is going through the motions. Classmates point out she has a talent for writing based on her translation of Country Roads and she obviously has a love of narrative fiction based on her reading habits over summer vacation; but she doesn’t particularly latch onto these aspects of herself or her life. It is only when she witnesses Seiji’s violin-making that she realizes her own aimlessness and develops a desire to write her own story as a way to match and relate to Seiji. If Seiji can aspire to an apprenticeship in Cremona, what’s stopping her from dedicating herself to the craft of writing?

The fate of the artisan.

Seiji in general becomes somewhat of a symbol in this film for the lost societal role of the artisan. His pursuit of the apprenticeship model of craftsmen education, something once commonplace in Europe and Japan but now almost entirely obsolete, is a complete contemporary fantasy that can no longer be achieved by most people. As such, Shizuku upon witnessing his passion is driven to pursue a similar kind of grand fantasy of the young novelist holed up in libraries and bedrooms scribbling away at their manuscript. When this fantasy clashes with reality and her grades start to slip, she is confronted by her family members and in another moment of this film’s idealistic and kind nature, her father agrees to let her continue her project until she is satisfied.

Throughout the film, the audience is shown this recurring image from Shizuku’s research of a violin maker looking sadly up at a window from within a room where he toils away at his craft. This visual motif of the artisan reoccurs while Shizuku grinds away in writing her own novel. With full dedication to a craft comes a certain amount of isolation, of loneliness and exhaustion. In the pursuit of this ideal of the artisan, Shizuku comes to realize the modern impracticalities that come with that kind of artistic pursuit. Her final novel is a rough gem in need of polishing as the owner of the antique shop puts it. Chutzpah and a singular focus aren’t enough for her to be a great novelist. As a fourteen year old girl, she neither has the time or life experience to create a great novel. As such, the resolution of the film is about Shizuku taking a pragmatic stance. Unlike Seiji, Shizuku can’t turn away from the realities of modern life–her sister is moving out and she’ll have to support her mother around the apartment while she finishes her graduate studies–but she can still pursue her passion while using the current education system as a way to help her aim for her goal of becoming an author.

As a film, Whisper of the Heart is incredibly kind and compassionate toward young artists. It on one hand validates their ambitions, their awakenings, the awe that comes with discovering a passion, but also acknowledges the hardships and limitations of their pursuits within the modern, capitalist world. Compulsory education, the limitations of the nuclear family needing to make ends meet and keep their homes in order, the lack of apprenticeship–these are all barriers in pursuing an artistic craft in the modern day. Still, Whisper of the Heart seems to argue through the budding romance between Seiji and Shizuku, Shizuku’s discovery of her passion, and the beautiful craftsmanship behind the Baron and other items in the antique shop that aspiring to be an artist is worth doing. The city may be sprawling and vast, but within its labyrinthine construction are niche spaces like the antique shop where artistic community and camaraderie can be found. The modern urban world is not entirely hostile–it is also a site of discovery and beauty, friendship and romance.

It’s for these reasons that I resonate so much with the film. I grew up in a sleepy suburb outside a major metropolitan area. I can’t claim to understand the experience of being a pre-teen growing up in a metropolis like Tokyo, but I can understand the transition point from merely being interested in a craft and then dedicating yourself to pursue it. Throughout my life, the pressures of our modern capitalist world have ebbed and flowed in such a way that I have drifted back and forth from being a “serious writer.” Whenever I feel down about the struggles related to that, the reality that I’ll likely never be able to professionally pursue and live off my passions, I remember the joy of creative awakening Shizuku experiences in Whisper of the Heart. Although the exact moment of my own awakening with writing has blurred and shifted in my head, that sensation and rush of dedicating yourself so fully to a project that it consumes your everyday tasks and thoughts is something I feel in my bones. There aren’t many pieces of art that accurately capture that hyperspecific moment with such care, delicacy, and warmth. And that’s also why I want Whisper of the Heart to be viewed as more than just the movie with the Baron or the origins of the lo-fi beats girl.

Sources Referenced:

"Why Shojo Manga Now?" Reprinted English translation, from Starting Point: 1979-1996, published by VIZ Media LLC.